Ordinary Least Squares#

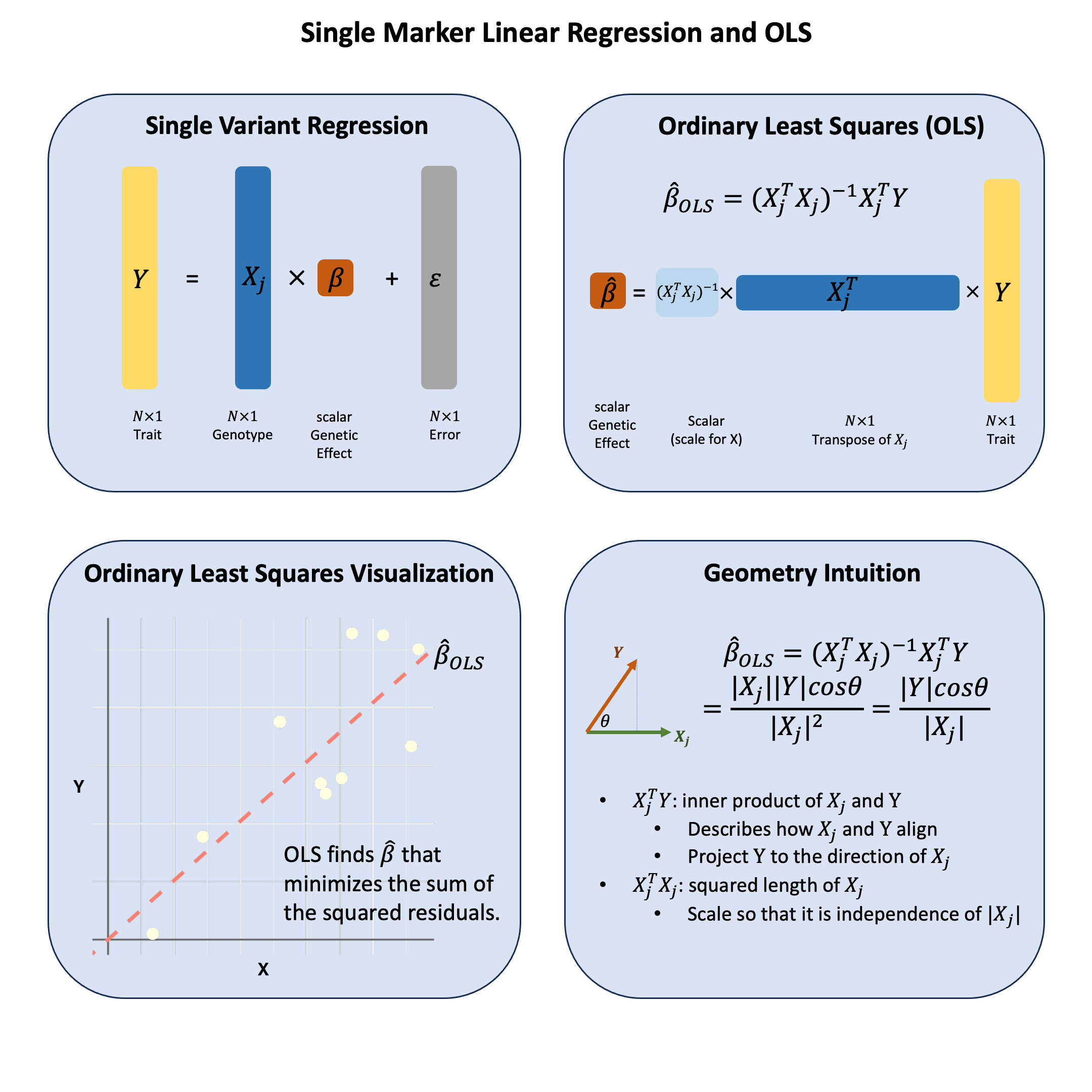

Single marker linear regression measures how well a genetic variant “aligns” with a trait by projecting the trait values onto the variant’s genotype direction.

Graphical Summary#

Key Formula#

In the single marker linear regression

\(\mathbf{Y}\) is the \(N \times 1\) vector of trait values for \(N\) individuals

\(\mathbf{X}\) is the \(N \times 1\) vector of the genotype vector for a single variant across \(N\) individuals

\(\beta\) is the scalar representing the effect size for the variant (to be estimated)

\(\boldsymbol{\epsilon} \sim N(\mathbf{0}, \sigma^2)\) is the \(N \times 1\) vector of error terms for \(N\) individuals

Using ordinary least squares (OLS), we can derive the estimators for \(\beta\) as:

Technical Details#

Genomic Intuition#

The OLS estimator has a beautiful geometric interpretation that makes intuitive sense in genomics: OLS measures how much two vectors align in the same direction through their inner product, scaled by the variance of \(\mathbf{X}\).

The Inner Product \(\mathbf{X}^T\mathbf{Y}\): This measures the projection of the phenotype vector \(\mathbf{Y}\) onto the genotype vector \(\mathbf{X}\). In genomic terms, it captures how much the phenotype and genotype “move together” - when genotype values are high, are phenotype values also high? The inner product quantifies this concordance.

Why the Scaling Factor \((\mathbf{X}^T\mathbf{X})^{-1}\)?: This normalization is crucial because we want our measure of association to be scale-independent. Whether we code genotypes as (0,1,2) or (0,2,4), or measure height in centimeters versus meters, the strength of association shouldn’t change due to arbitrary scaling choices. The factor \((\mathbf{X}^T\mathbf{X})^{-1} = \frac{1}{\sum_{i=1}^N X_i^2}\) normalizes by the squared magnitude of the genotype vector, making the coefficient invariant to arbitrary scaling.

The Complete Picture: OLS finds the scalar that best aligns the genotype vector with the phenotype vector. It asks: “How much should I scale \(\mathbf{X}\) so it points as closely as possible toward \(\mathbf{Y}\)?” The answer is \(\hat{\beta}_\text{OLS}\).

Simplified Form for Single Marker Regression#

For a single marker regression, the OLS estimator simplifies to:

If genotypes are standardized (mean-centered and scaled to variance = 1), this becomes the sample covariance:

Unbiasedness#

Under the assumption that \(E[\epsilon|\mathbf{X}] = 0\):

The OLS estimator is unbiased for the true effect size.

Special Case: Centered Variables#

When both \(\mathbf{X}\) and \(\mathbf{Y}\) are mean-centered (\(\bar{X} = 0\), \(\bar{Y} = 0\)), the regression simplifies to regression through the origin.

Slope estimator: \(\hat{\beta}_{\text{OLS}} = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^N X_i Y_i}{\sum_{i=1}^N X_i^2}\)

Variance of the estimator: \(\text{Var}(\hat{\beta}_{\text{OLS}}) = \sigma^2 \cdot \frac{1}{\sum_{i=1}^N X_i^2} = \frac{\sigma^2}{\sum_{i=1}^N X_i^2}\)

Standard error: \(\text{SE}(\hat{\beta}_{\text{OLS}}) = \sqrt{\frac{\hat{\sigma}^2}{\sum_{i=1}^N X_i^2}}\)

where \(\hat{\sigma}^2 = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^N (Y_i - \hat{Y}_i)^2}{N-1}\) is the residual variance estimate. We use \(N-1\) degrees of freedom because we estimate only one parameter (the slope) when variables are centered.

Sample Size Requirements#

Absolute minimum: \(N \geq\) number of parameters to estimate

For regression through origin (centered case): \(N \geq 1\) technically, but \(N \geq 2\) for any practical inference

For regression with intercept: \(N \geq 2\)

Matrix \(\mathbf{X}^T\mathbf{X}\) must be invertible (full column rank required)

Larger \(N\) improves estimate precision and reduces uncertainty

In practice, for reliable inference, generally \(N \geq 30\) (rule of thumb)

Example#

In our toy example data of 5 individuals, now say we have also observed the height information for the 5 individuals. How do we actually perform OLS analysis to answer the question: do any of these variants actually influence height?

To begin with, we still converted those nucleotides into numbers as we did in Lecture: genotype coding, and after the transformation of the genotypes using an additive model, we apply our OLS formula both manually and using R’s built-in function. This will show you exactly how that geometric intuition - the projection and alignment between genotype and phenotype vectors - translates into real code and results.

Setup#

# Clear the environment

rm(list = ls())

# Define genotypes for 5 individuals at 3 variants

# These represent actual alleles at each position

# For example, Individual 1 has genotypes: CC, CT, AT

genotypes <- c(

"CC", "CT", "AT", # Individual 1

"TT", "TT", "AA", # Individual 2

"CT", "CT", "AA", # Individual 3

"CC", "TT", "AA", # Individual 4

"CC", "CC", "TT" # Individual 5

)

# Reshape into a matrix

N = 5

M = 3

geno_matrix <- matrix(genotypes, nrow = N, ncol = M, byrow = TRUE)

rownames(geno_matrix) <- paste("Individual", 1:N)

colnames(geno_matrix) <- paste("Variant", 1:M)

alt_alleles <- c("T", "C", "T")

# Convert to raw genotype matrix using the additive model

Xraw_additive <- matrix(0, nrow = N, ncol = M) # count number of non-reference alleles

rownames(Xraw_additive) <- rownames(geno_matrix)

colnames(Xraw_additive) <- colnames(geno_matrix)

for (i in 1:N) {

for (j in 1:M) {

alleles <- strsplit(geno_matrix[i,j], "")[[1]]

Xraw_additive[i,j] <- sum(alleles == alt_alleles[j])

}

}

X <- scale(Xraw_additive, center = TRUE, scale = TRUE)

We observe the heights (\(Y\)) for the five individuals as follows, and scale \(Y\) as well:

# assign observed height for the 5 individuals

Y_raw <- c(180, 160, 158, 155, 193)

Y <- scale(Y_raw)

OLS Regression#

We perform OLS analysis on each single SNP using lm function in R:

p_values <- numeric(M) # Store p-values

betas <- numeric(M) # Store estimated effect sizes

for (j in 1:M) {

SNP <- X[, j] # Extract genotype for SNP j

model <- lm(Y ~ SNP) # OLS regression: Trait ~ SNP

summary_model <- summary(model)

# Store p-value and effect size (coefficient)

p_values[j] <- summary_model$coefficients[2, 4] # p-value for SNP effect

betas[j] <- summary_model$coefficients[2, 1] # Estimated beta coefficient

}

The OLS results are:

OLS_results <- data.frame(Variant = colnames(X), Beta = betas, P_Value = p_values)

OLS_results

| Variant | Beta | P_Value |

|---|---|---|

| <chr> | <dbl> | <dbl> |

| Variant 1 | -0.5000913 | 0.390901513 |

| Variant 2 | 0.8525024 | 0.066475513 |

| Variant 3 | 0.9866667 | 0.001844466 |

Analytical Calculation of \(\beta\)#

Or we can use the formula to calculate \(\beta\) directly:

# Calculate betahat for a single SNP explicitly

calculate_beta_ols <- function(Y, X) {

# beta_hat = (X^T X)^(-1) X^T Y

beta_hat <- solve(t(X) %*% X) %*% t(X) %*% Y

return(beta_hat)

}

# Perform GWAS-style analysis: Test each SNP independently using OLS

betas_formula <- numeric(M)

for (j in 1:M) {

betas_formula[j] <- calculate_beta_ols(Y, X[,j, drop=FALSE])

}

Comparison of Results#

We compare the results calculated from the lm function and from the formula, and as expected they are the same:

OLS_results$Beta_from_formula = betas_formula

OLS_results

| Variant | Beta | P_Value | Beta_from_formula |

|---|---|---|---|

| <chr> | <dbl> | <dbl> | <dbl> |

| Variant 1 | -0.5000913 | 0.390901513 | -0.5000913 |

| Variant 2 | 0.8525024 | 0.066475513 | 0.8525024 |

| Variant 3 | 0.9866667 | 0.001844466 | 0.9866667 |

Supplementary#

Graphical Summary#

# Load necessary library

library(ggplot2)

options(repr.plot.width = 10, repr.plot.height = 6)

# Generate positive example data

set.seed(42)

x <- runif(10, min = 0, max = 5) # Positive x values

y <- 0.5 * x + rnorm(10, mean = 0, sd = 1)

y <- y - min(y) + 0.1 # Ensure y is positive

data <- data.frame(x = x, y = y)

# Fit linear model through the origin

model <- lm(y ~ 0 + x, data = data) # No intercept

beta1 <- coef(model)[1]

# Plot

p <- ggplot(data, aes(x = x, y = y)) +

geom_hline(yintercept = 0, color = "gray40", linewidth = 1) +

geom_vline(xintercept = 0, color = "gray40", linewidth = 1) +

geom_point(color = "lightyellow", size = 6) + # yellow points

geom_abline(intercept = 0, slope = beta1, color = "salmon", linetype = "dashed", linewidth = 2) +

labs(x = "X", y = "Y") +

theme_minimal(base_size = 18) +

theme(

plot.title = element_blank(), # no title

axis.title = element_text(size = 20, face = "bold"),

axis.text = element_blank(),

axis.ticks = element_blank(),

axis.title.y = element_text(angle = 0, vjust = 0.5) # horizontal Y label

)

print(p)

# Save with transparent background

ggsave("./figures/ordinary_least_squares.png", plot = p,

width = 6, height = 6,

bg = "transparent",

dpi = 300)