Confounder#

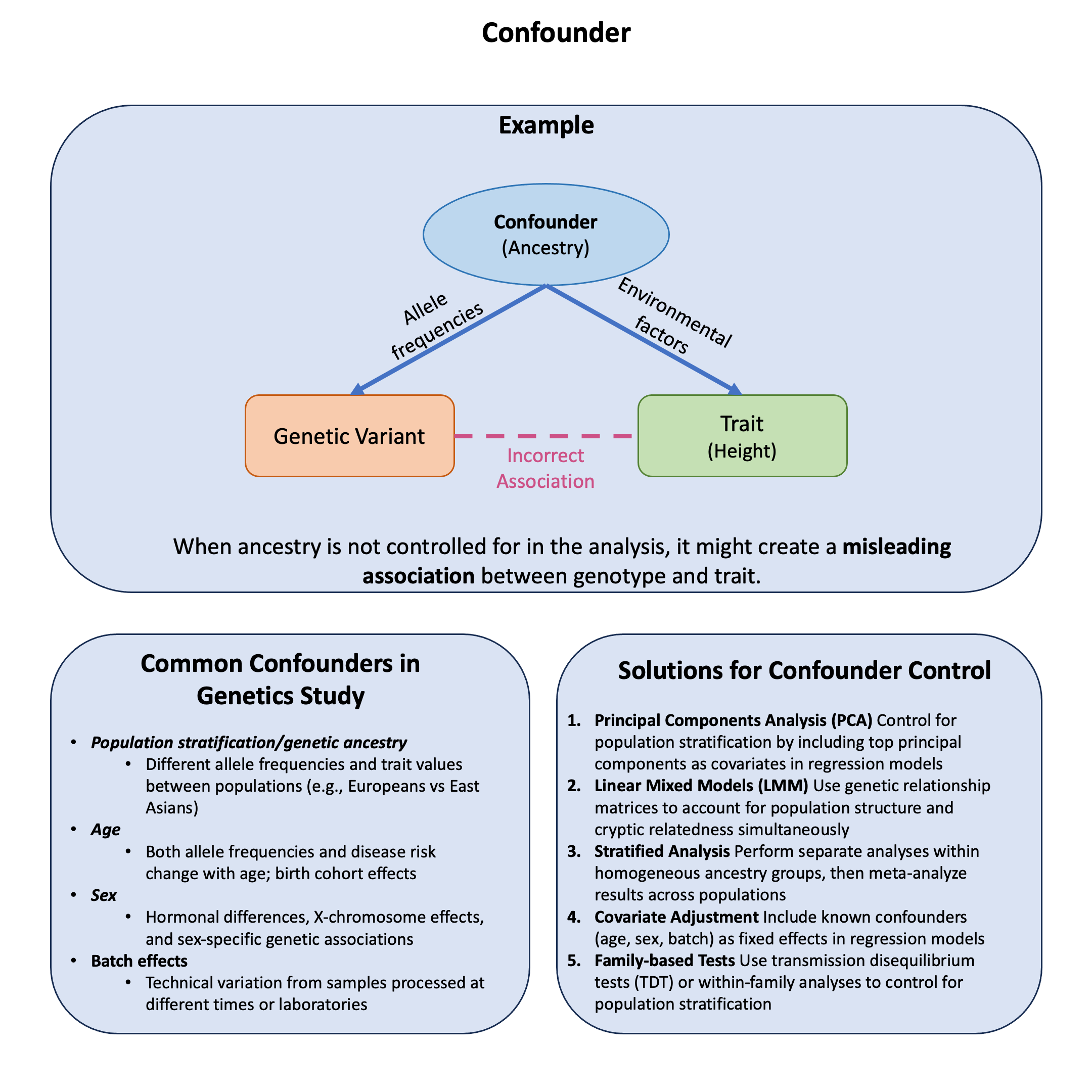

A confounder is a variable that influences both the exposure and outcome independently, creating a misleading association between them that doesn’t represent a true causal relationship.

Graphical Summary#

Key Formula#

The key formula for the concept of a confounder is represented in a causal diagram as:

Where:

\(W\) is the confounder variable

\(X\) is the exposure/treatment variable

\(Y\) is the outcome variable

The arrows \((\leftarrow, \rightarrow)\) indicate the direction of causal influence

This diagram illustrates that a confounder (\(W\)) has a direct causal effect on both the exposure (\(X\)) and the outcome (\(Y\)), creating a “backdoor path” between \(X\) and \(Y\) that must be blocked to obtain an unbiased estimate of the causal effect.

Technical Details#

Observed Association vs. True Effect#

When a confounder is present but not controlled:

True Effect: The real biological relationship we want to find

Confounding Bias: The false association created by the confounder

Observed Association: What we actually measure (often misleading!)

The Solution: Control for Confounders#

The most common and practical solution is regression adjustment - simply include confounders as additional variables in your model:

Where \(W_1, W_2, \ldots\) are confounders (e.g., age, ancestry, sex) and \(\beta_1\) is the unbiased effect of genetic variant \(X\).

Here are the common approaches in genetic studies:

Principal Components (Most Common): Control for population structure by including top PCs:

\[ \mathbf{Y} = \mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\beta} + \text{PC}1 + \text{PC}2 + \text{PC}3 + \text{Age} + \text{Sex} \]Linear Mixed Models: Use genetic relationship matrices for complex population structure:

\[ \mathbf{Y} = \mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\beta} + \mathbf{g} + \boldsymbol{\epsilon}, \quad \mathbf{g} \sim N(0, \sigma_g^2 \mathbf{G}) \]Stratified Analysis: Analyze each ancestry group separately, then meta-analyze results:

The goal is to block backdoor paths while perserving the direct causal path.

Example#

Recall from our earlier discussion in Example 2 in Lecture: marginal and joint effects about how a genetic variant can appear protective when analyzed alone but harmful when controlling for other factors. This dramatic reversal illustrates confounding - where ancestry affects both variant frequency and disease risk, creating spurious associations.

The key question: How can ancestry confound genetic associations and lead us to completely misinterpret a variant’s true effect?

Setup#

rm(list = ls())

set.seed(9)

N <- 100

# Create a confounding variable (genetic ancestry)

ancestry <- rbinom(N, 1, 0.5) # 0 = Population A, 1 = Population B

# Generate genotype that's correlated with ancestry

# Population B has higher frequency of risk allele

variant1 <- ifelse(ancestry == 0,

rbinom(sum(ancestry == 0), 2, 0.2), # Pop A: low risk allele frequency

rbinom(sum(ancestry == 1), 2, 0.8)) # Pop B: high risk allele frequency

# Check allele frequencies by population

cat("Population A (ancestry=0) mean genotype:", round(mean(variant1[ancestry == 0]), 2), "\n")

cat("Population B (ancestry=1) mean genotype:", round(mean(variant1[ancestry == 1]), 2), "\n")

# Population B has generally lower disease risk (better healthcare/environment)

# But the variant increases risk within each population

baseline_risk <- ifelse(ancestry == 0, 0.8, 0.1) # Pop A much higher baseline risk

genetic_effect <- 0.1 * variant1 # Variant increases risk in both populations

disease_prob <- baseline_risk + genetic_effect

disease <- rbinom(N, 1, pmin(disease_prob, 1)) # Ensure prob ≤ 1

# Create data frame

data <- data.frame(

disease = disease,

variant1 = variant1,

ancestry = ancestry

)

Population A (ancestry=0) mean genotype: 0.41

Population B (ancestry=1) mean genotype: 1.59

Analysis 1: Ignore Genetic Ancestry#

In Example 2 of Lecture: marginal and joint effects, when the genetic ancestry is not considered in the model, the variant appears to be protective:

# Combining both ancestries and perform analysis

model_combined_ancestries <- glm(disease ~ variant1, data = data, family = binomial)

OR_combined_ancestries <- exp(coef(model_combined_ancestries)[2])

p_combined_ancestries <- summary(model_combined_ancestries)$coefficients[2, 4]

cat("=== ESTIMATED EFFECT (combining genetic ancestries) ===\n")

cat("OR =", round(OR_combined_ancestries, 3), ", p =", round(p_combined_ancestries, 4), "\n")

cat("Interpretation:", ifelse(OR_combined_ancestries > 1, "Detrimental ", "Protective"), "\n")

=== ESTIMATED EFFECT (combining genetic ancestries) ===

OR = 0.394 , p = 4e-04

Interpretation: Protective

Analysis 2: Considering Confounder#

But if we consider the confounder in the model, we will get the correct answer (rather than the Simpson’s paradox that we see in Example 2 in Lecture: marginal and joint effects):

# Combining both ancestries but including ancestry as a covariate

model_controlled <- glm(disease ~ variant1 + ancestry, data = data, family = binomial)

OR_controlled <- exp(coef(model_controlled)[2])

p_controlled <- summary(model_controlled)$coefficients[2, 4]

cat("=== JOINT EFFECT (combining populations, and considering ancestry) ===\n")

cat("OR =", round(OR_controlled, 3), ", p =", round(p_controlled, 4), "\n")

cat("Interpretation:", ifelse(OR_controlled > 1, "Detrimental ", "Protective"), "\n")

=== JOINT EFFECT (combining populations, and considering ancestry) ===

OR = 1.192 , p = 0.6768

Interpretation: Detrimental