Likelihood Ratio#

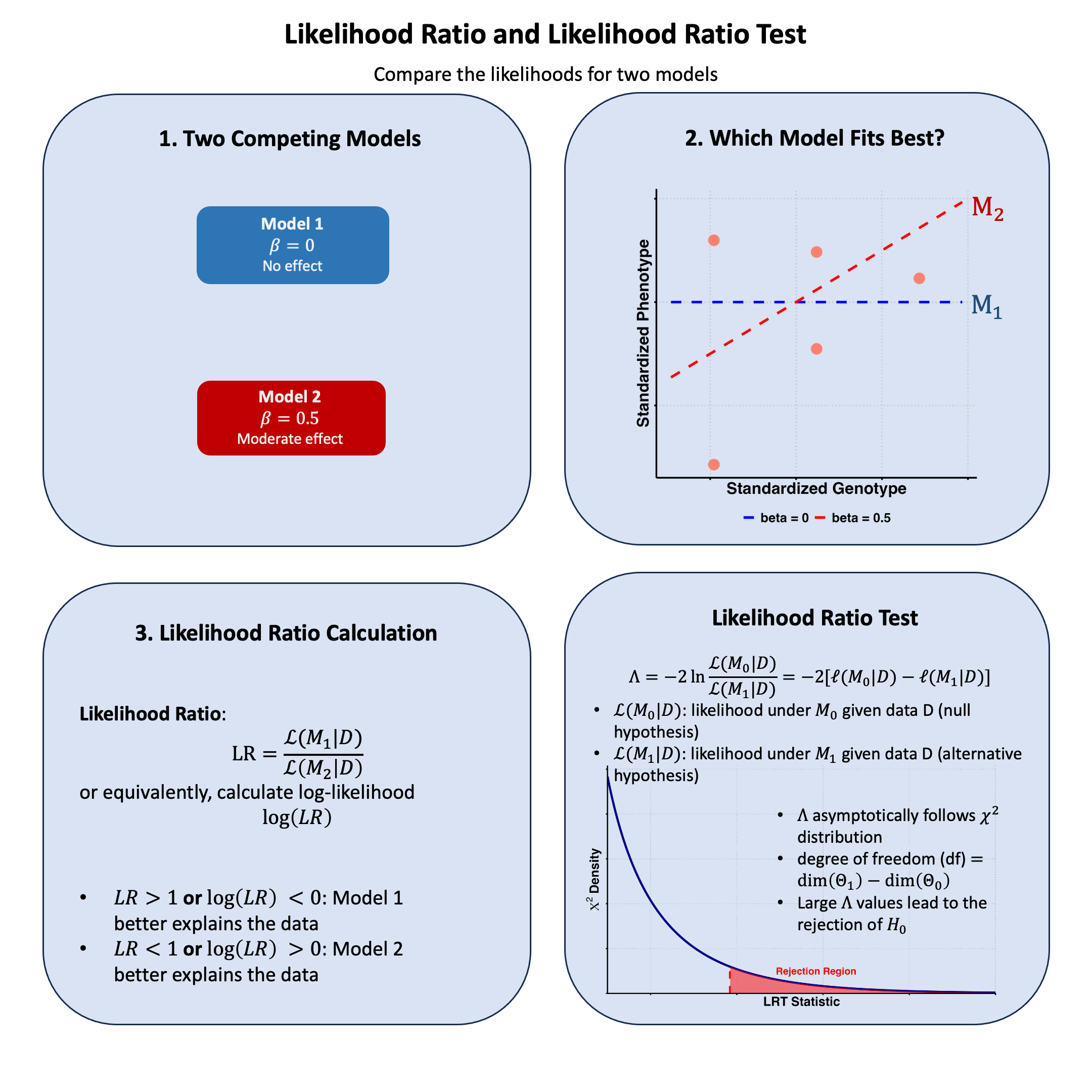

The likelihood ratio quantifies how much more probable our observed data is under one model compared to another, providing a natural way to choose between competing explanations of the data.

Graphical Summary#

Key Formula#

The likelihood ratio between Model 1 and Model 2 is:

Where:

\(\text{LR}\) is the likelihood ratio

\(\text{D}\) represents the observed data

\(\mathcal{L}(\text{M}_1 \mid \text{D})\) is the likelihood function for Model 1 \(\text{M}_1\) given data \(\text{D}\)

\(\mathcal{L}(\text{M}_2 \mid \text{D})\) is the likelihood function for Model 2 \(\text{M}_2\) given data \(\text{D}\)

Technical Details#

Basic Interpretation#

For the likelihood ratio (\(\text{LR}\)):

\(\text{LR} > 1\): Model 1 better explains the data

\(\text{LR} < 1\): Model 2 better explains the data

\(\text{LR} = 1\): Both models explain the data equally well

The likelihood ratio quantifies the relative evidence for one model compared to another, providing a direct way to compare competing hypotheses based on the observed data.

Properties#

The likelihood ratio is always non-negative (because likelihood is always between 0 and 1): \(\text{LR} \geq 0\)

Can be used to compare any two models

Forms the basis for many statistical tests and model selection criteria, e.g., testing association between variants and traits

Wilks’ Theorem#

Let’s assume we are dealing with models parameterized by \(\theta\). To generalize the case of simple hypotheses, let’s assume that \(H_0\) specifies that \(\theta\) lives in some set \(\Theta_0\) and \(H_1\) specifies that \(\theta \in \Theta_1\). Let \(\Omega = \Theta_0 \cup \Theta_1\). A somewhat natural extension to the likelihood ratio test statistic we discussed above is the generalized log-likelihood ratio:

For technical reasons, it is preferable to use the following related quantity:

Just like before, larger values of \(\Lambda_n\) provide stronger evidence against \(H_0\).

Wilks’s Theorem states that, suppose that the dimension of \(\Omega\) is \(v\) and the dimension of \(\Theta_0\) is \(r\). Under regularity conditions and assuming \(H_0\) is true, the distribution of \(\Lambda_n\) tends to a chi-squared distribution with degrees of freedom equal to \(v−r\) as the sample size tends to infinity.

With this theorem in hand (and for \(n\) large), we can compare the value of our log-likehood ratio to the expected values from a \(\chi^2_{v−r}\) distribution.

Likelihood Ratio Test#

The likelihood ratio test (LRT) compares nested models to test whether a more complex model provides a significantly better fit than a simpler one.

Test Statistic:

where \(\text{M}_0\) is the null (simpler) model and \(\text{M}_1\) is the alternative (more complex) model.

According to Wilks’ Theorem, under regularity conditions, \(\Lambda\) asymptotically follows \(\chi^2_{\text{df}}\) where \(\text{df}\) is the difference in the number of parameters between the two models. Given significance level \(\alpha\), reject \(H_0\) if \(\Lambda > \chi^2_{\text{df},\alpha}\).

Key Limitations:

Nested models required – Cannot compare non-nested models

Counterexample: Comparing different genetic variants (Variant A vs. Variant B) is invalid because neither model is a subset of the other (i.e., non-nested)

You can compute the likelihood ratio, but you cannot conduct a valid likelihood ratio test

Asymptotic approximation – May perform poorly with small sample sizes

Regularity conditions – Must be satisfied for chi-square approximation to hold

Multiple testing – Requires correction when performing many simultaneous tests

Example#

In Lecture: likelihood, we compared three genetic effect models using likelihood. Now we extend this analysis to answer: Is the observed effect statistically significant, or just random noise?

Using the same genetic data (true effect \(\beta = 0.4\)), we’ll:

Compare models using likelihood ratios

Find the optimal parameter via maximum likelihood estimation

Test significance using the likelihood ratio test

This pipeline demonstrates the complete workflow from parameter estimation to hypothesis testing.

Setup#

Let’s first generate the genotype data and trait values for 5 individuals.

# Clear the environment

rm(list = ls())

library(ggplot2)

set.seed(19) # For reproducibility

# Generate genotype data for 5 individuals at a single variant

N <- 5

genotypes <- c("CC", "CT", "TT", "CT", "CC") # Individual genotypes

names(genotypes) <- paste("Individual", 1:N)

# Define alternative allele

alt_allele <- "T"

# Convert to additive genotype coding (count of alternative alleles)

Xraw_additive <- numeric(N)

for (i in 1:N) {

alleles <- strsplit(genotypes[i], "")[[1]]

Xraw_additive[i] <- sum(alleles == alt_allele)

}

names(Xraw_additive) <- names(genotypes)

# Standardize genotypes

X <- scale(Xraw_additive, center = TRUE, scale = TRUE)[,1]

# Set true beta and generate phenotype data

true_beta <- 0.4

true_sd <- 1.0

# Generate phenotype with true effect

Y <- X * true_beta + rnorm(N, 0, true_sd)

Likelihood and Log-likelihood#

Now, let’s create two functions to compute the likelihood and log-likelihood under different models (in this case, different \(\beta\)s) for the effect of a genetic variant on the phenotype:

# Likelihood function for normal distribution

likelihood <- function(beta, sd, X, Y) {

# Calculate expected values under the model

mu <- X * beta

# Calculate likelihood (product of normal densities)

prod(dnorm(Y, mean = mu, sd = sd, log = FALSE))

}

# Log-likelihood function (more numerically stable)

log_likelihood <- function(beta, sd, X, Y) {

# Calculate expected values under the model

mu <- X * beta

# Calculate log-likelihood (sum of log normal densities)

sum(dnorm(Y, mean = mu, sd = sd, log = TRUE))

}

Now, let’s apply this function to our three models:

# Test three different models with different beta values

beta_values <- c(0, 0.5, 1.0) # Three different effect sizes to test

model_names <- paste0("Model ", 1:3, " (beta = ", beta_values, ")")

# Calculate likelihoods and log-likelihoods

results <- data.frame(

Model = model_names,

Beta = beta_values,

Likelihood = numeric(3),

Log_Likelihood = numeric(3)

)

for (i in 1:3) {

results$Likelihood[i] <- likelihood(beta = beta_values[i], sd = true_sd, X = X, Y = Y)

results$Log_Likelihood[i] <- log_likelihood(beta = beta_values[i], sd = true_sd, X = X, Y = Y)

}

print("Likelihood and Log-Likelihood Results:")

results

[1] "Likelihood and Log-Likelihood Results:"

| Model | Beta | Likelihood | Log_Likelihood |

|---|---|---|---|

| <chr> | <dbl> | <dbl> | <dbl> |

| Model 1 (beta = 0) | 0.0 | 0.0019210299 | -6.254894 |

| Model 2 (beta = 0.5) | 0.5 | 0.0021961524 | -6.121048 |

| Model 3 (beta = 1) | 1.0 | 0.0009236263 | -6.987203 |

Now let’s calculate the likelihood ratios between each pair of models:

# Calculate all pairwise likelihood ratios

model_pairs <- combn(1:3, 2) # All combinations of 2 models from 3

n_pairs <- ncol(model_pairs)

lr_results <- data.frame(

Comparison = character(n_pairs),

LR = numeric(n_pairs),

Log_LR = numeric(n_pairs),

Interpretation = character(n_pairs),

stringsAsFactors = FALSE

)

for (i in 1:n_pairs) {

m1 <- model_pairs[1, i] # First model index

m2 <- model_pairs[2, i] # Second model index

# Calculate likelihood ratio: L(M1|D) / L(M2|D)

lr_value <- results$Likelihood[m1] / results$Likelihood[m2]

log_lr_value <- results$Log_Likelihood[m1] - results$Log_Likelihood[m2]

# Determine interpretation

if (lr_value > 1) {

interpretation <- paste("Model", m1, "better supported")

} else if (lr_value < 1) {

interpretation <- paste("Model", m2, "better supported")

} else {

interpretation <- "Equal support"

}

# Store results

lr_results$Comparison[i] <- paste("Model", m1, "vs Model", m2)

lr_results$LR[i] <- lr_value

lr_results$Log_LR[i] <- log_lr_value

lr_results$Interpretation[i] <- interpretation

}

The results are:

lr_results

| Comparison | LR | Log_LR | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| <chr> | <dbl> | <dbl> | <chr> |

| Model 1 vs Model 2 | 0.8747253 | -0.1338454 | Model 2 better supported |

| Model 1 vs Model 3 | 2.0798778 | 0.7323091 | Model 1 better supported |

| Model 2 vs Model 3 | 2.3777498 | 0.8661546 | Model 2 better supported |

The likelihood ratios reveal clear patterns in model support:

Model 2 (\(\beta = 0.5\)) receives strongest support, being 1.14× more likely than Model 1 and 2.38× more likely than Model 3

Model 1 (\(\beta = 0\)) is 2.08× more likely than Model 3 (\(\beta = 1.0\)), suggesting no effect is more plausible than a large effect

This ranking makes sense given the true effect (\(\beta = 0.4\)) used to generate the data: Model 2 is closest to the truth, followed by Model 1, while Model 3 substantially overestimates the genetic effect.

Likelihood Ratio Test#

From our results, we see that Model 2 (\(\beta\) = 0.5) has the highest likelihood among our three tested values. But for a proper likelihood ratio test, we need to compare the null hypothesis (\(\beta\) = 0) against the best possible alternative - which means we need to find the Maximum Likelihood Estimate (MLE).

The LRT framework is:

\(H_0\): \(\beta = 0\) (no genetic effect)

\(H_1\): \(\beta \neq 0\) (genetic effect exists - best estimate is the MLE)

# First, find the MLE to get the best possible alternative model

mle_result <- optimize(log_likelihood,

interval = c(-2, 2),

maximum = TRUE,

sd = true_sd, X = X, Y = Y)

beta_mle <- mle_result$maximum

log_lik_mle <- mle_result$objective

cat("MLE: beta =", round(beta_mle, 4), "\n")

cat("Log-likelihood at MLE:", round(log_lik_mle, 4), "\n")

MLE: beta = 0.3169

Log-likelihood at MLE: -6.054

Now we can conduct the LRT:

# Now conduct the LRT: MLE vs Null

log_lik_null <- log_likelihood(beta = 0, sd = true_sd, X = X, Y = Y)

cat("\nLikelihood Ratio Test:\n")

cat("H0: beta = 0\n")

cat("H1: beta != 0 (MLE)\n\n")

# Calculate LRT statistic

lrt_statistic <- -2 * (log_lik_null - log_lik_mle)

df <- 1 # difference in number of free parameters

# Calculate p-value

p_value <- pchisq(lrt_statistic, df = df, lower.tail = FALSE)

cat("Log-likelihood (Null):", round(log_lik_null, 4), "\n")

cat("Log-likelihood (MLE):", round(log_lik_mle, 4), "\n")

cat("LRT Statistic:", round(lrt_statistic, 4), "\n")

cat("p-value:", round(p_value, 4), "\n")

# Statistical decision

alpha <- 0.05

if (p_value < alpha) {

cat("Result: REJECT null - significant evidence for genetic effect\n")

} else {

cat("Result: FAIL TO REJECT null - insufficient evidence for genetic effect\n")

}

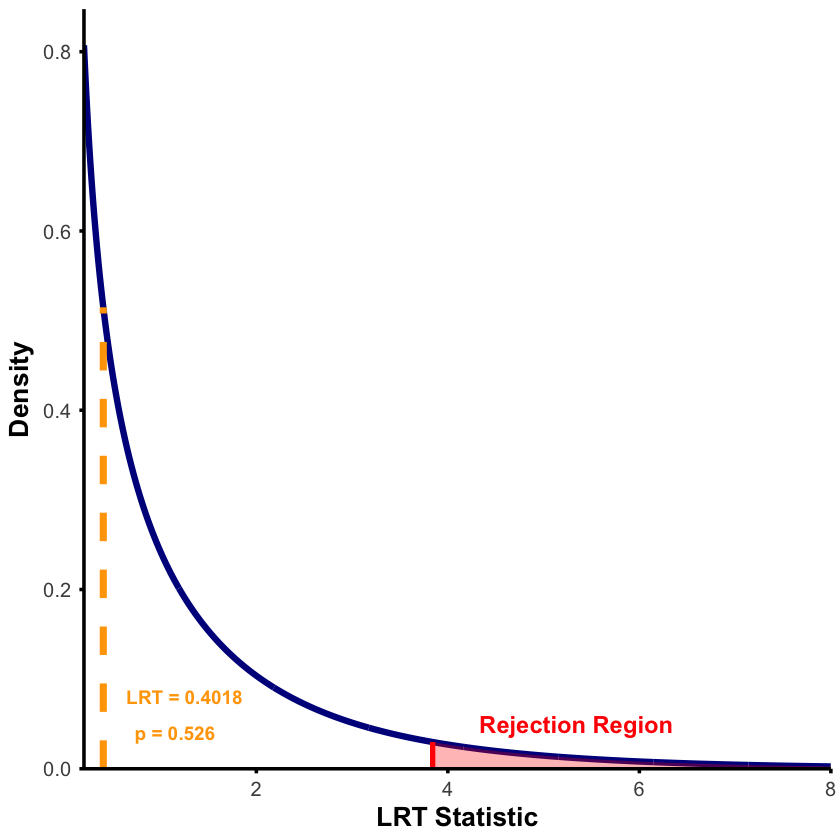

Likelihood Ratio Test:

H0: beta = 0

H1: beta != 0 (MLE)

Log-likelihood (Null): -6.2549

Log-likelihood (MLE): -6.054

LRT Statistic: 0.4018

p-value: 0.5262

Result: FAIL TO REJECT null - insufficient evidence for genetic effect

Note that we can also use the qchisq function in R to compute the critical value corresponding to a given significance level (in this case, 0.95) and degrees of freedom, and we compare to the LRT results:

# Parameters

x_vals <- seq(0.2, 8, length.out = 1000)

chi_sq_density <- dchisq(x_vals, df = df)

critical_value <- qchisq(0.95, df = df)

# Data frames

df_chi <- data.frame(x = x_vals, density = chi_sq_density)

df_reject <- subset(df_chi, x >= critical_value)

# Plot

p_lrt <- ggplot(df_chi, aes(x = x, y = density)) +

geom_line(color = "darkblue", linewidth = 1.8) +

geom_area(data = df_reject, aes(x = x, y = density),

fill = "red", alpha = 0.3) +

# Critical value line

annotate("segment", x = critical_value, xend = critical_value,

y = 0, yend = dchisq(critical_value, df),

color = "red", linewidth = 1.5) +

# Observed LRT statistic line

annotate("segment", x = lrt_statistic, xend = lrt_statistic,

y = 0, yend = dchisq(lrt_statistic, df),

color = "orange", linetype = "dashed", linewidth = 2) +

# Labels

annotate("text", x = lrt_statistic + 0.85, y = max(chi_sq_density) * 0.1,

label = paste("LRT =", round(lrt_statistic, 4)),

color = "orange", size = 4, fontface = "bold") +

annotate("text", x = lrt_statistic + 0.75, y = max(chi_sq_density) * 0.05,

label = paste("p =", round(p_value, 3)),

color = "orange", size = 4, fontface = "bold") +

annotate("text", x = critical_value + 1.5, y = 0.05,

label = "Rejection Region",

color = "red", size = 5, fontface = "bold") +

labs(x = expression(bold(LRT~Statistic)),

y = expression(bold(Density))) +

scale_x_continuous(expand = c(0, 0)) +

scale_y_continuous(expand = expansion(mult = c(0, 0.05))) +

theme_minimal() +

theme(

text = element_text(size = 14),

plot.title = element_text(size = 18, face = "bold", hjust = 0.5),

axis.title.x = element_text(size = 16, face = "bold"),

axis.title.y = element_text(size = 16, face = "bold"),

axis.text = element_text(size = 12),

panel.grid.major = element_blank(),

panel.grid.minor = element_blank(),

axis.line = element_line(linewidth = 1),

axis.ticks = element_line(linewidth = 1),

panel.background = element_rect(fill = "transparent", color = NA),

plot.background = element_rect(fill = "transparent", color = NA)

)

print(p_lrt)

# Save and display

ggsave("./figures/likelihood_LRT.png", plot = p_lrt,

width = 10, height = 6, dpi = 300, bg = "transparent")

The true effect size was \(\beta = 0.4\), and our MLE correctly estimated it (\(\hat{\beta} \approx 0.4\)), yet the LRT failed to detect statistical significance. This illustrates the distinction between effect size and statistical significance.

The issue is small sample size (n=5). While the effect exists and our estimate is accurate, there’s too much uncertainty to rule out random chance. Most genetic effects require hundreds or thousands of individuals to detect with statistical confidence.

A non-significant result doesn’t mean no effect exists - it means insufficient data to prove the effect beyond reasonable doubt.

Supplementary#

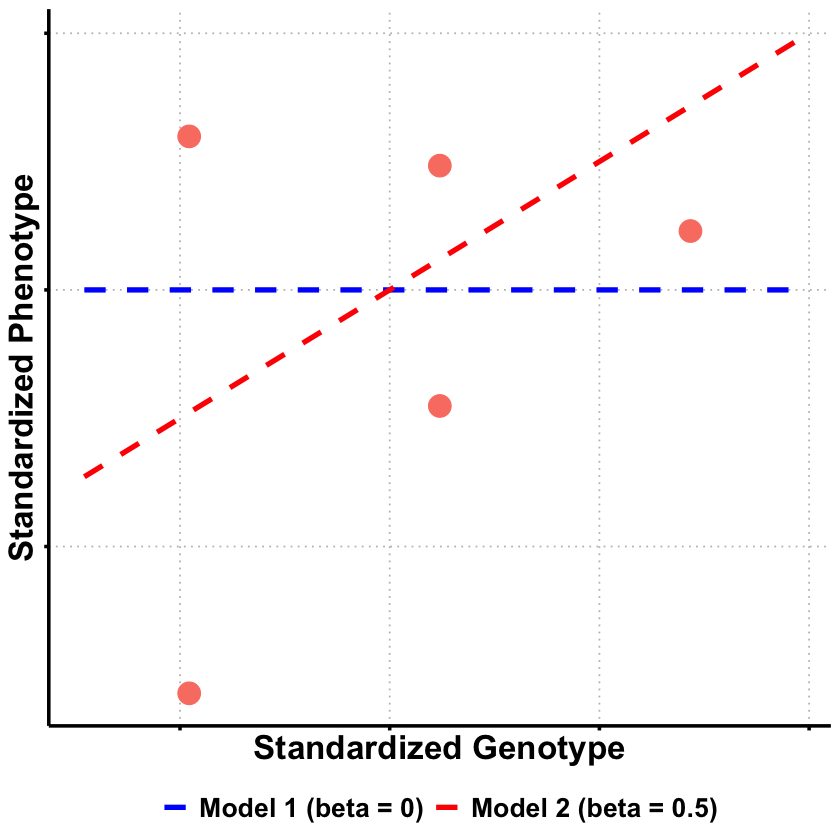

Graphical Summary#

library(dplyr)

# Prepare the data from our analysis

df_scatter <- data.frame(

Genotype = X,

Phenotype = Y

)

# Create sequence for smooth lines

x_vals <- seq(min(X) - 0.5, max(X) + 0.5, length.out = 100)

# Create data frame for regression lines using Model 1 (beta=0) and Model 2 (beta=0.5)

selected_betas <- c(0, 0.5)

lines_df <- data.frame(

Genotype = rep(x_vals, 2),

Phenotype = c(

selected_betas[1] * x_vals, # Model 1: beta = 0

selected_betas[2] * x_vals # Model 2: beta = 0.5

),

Model = factor(rep(c("Model 1 (beta = 0)", "Model 2 (beta = 0.5)"), each = length(x_vals)),

levels = c("Model 1 (beta = 0)", "Model 2 (beta = 0.5)"))

)

# Create plot

p <- ggplot(df_scatter, aes(x = Genotype, y = Phenotype)) +

geom_point(color = "salmon", size = 6) +

labs(

x = "Standardized Genotype",

y = "Standardized Phenotype"

) +

theme_minimal() +

theme(

text = element_text(size = 18, face = "bold"),

axis.title = element_text(size = 20, face = "bold"),

axis.text.x = element_blank(),

axis.text.y = element_blank(),

panel.grid.major = element_line(color = "gray", linetype = "dotted"),

panel.grid.minor = element_blank(),

axis.line = element_line(linewidth = 1),

axis.ticks = element_line(linewidth = 1),

panel.background = element_rect(fill = "transparent", color = NA),

plot.background = element_rect(fill = "transparent", color = NA)

) +

geom_line(data = lines_df, aes(x = Genotype, y = Phenotype, color = Model, linetype = Model), linewidth = 1.5) +

scale_color_manual(values = c("Model 1 (beta = 0)" = "blue", "Model 2 (beta = 0.5)" = "red")) +

scale_linetype_manual(values = c("Model 1 (beta = 0)" = "dashed", "Model 2 (beta = 0.5)" = "dashed")) +

theme(

legend.title = element_blank(),

legend.position = "bottom",

legend.text = element_text(size = 16, face = "bold")

)

# Show and save plot

print(p)

ggsave("./figures/likelihood_ratio.png", plot = p,

width = 6, height = 6, dpi = 300, bg = "transparent")

Extended Reading#

Likelihood Ratio: Wilks’s Theorem from Matthew Stephen’s fiveMinuteStats